He shaped a world of superpowers but to those without power he was ruthless. How did one diplomat hold sway for so long?

Henry Kissinger was a complicated, insecure man who believed the US alone could impose order in a complicated, insecure world. For almost a decade from 1969, at the height of cold war instability, he became the international face of America – a very political diplomat almost as well known as his patron, Richard Nixon, the then president.

Kissinger was also a Harvard academic and self-styled grand strategist, a student of Castlereagh and Metternich who put his amoral theories of “realist” foreign policy into practice with often horrific results. He viewed peoples and nations as movable, disposable pieces on a giant global chessboard. He was the bürgermeister of realpolitik.

Yet Kissinger had a very human side, too. As a German Jew from a middle–class Bavarian family who fled the Nazis in 1938, he was ever anxious for acceptance in his adoptive country. Contemporaries viewed him as manipulative, arrogant, secretive, yet strangely fond of the limelight. He loved power, which he deemed the greatest of aphrodisiacs.

Looking back after his death last week, aged 100, a yawning gulf is apparent between modern-day values and beliefs about the proper conduct of foreign policy and the very different Kissinger era. It’s clear the world has changed radically since then – and yet, in some ways, has not changed at all. Ultimately, the national interest still rules all.

Working as Nixon’s national security adviser from 1969, and as secretary of state from 1973, Kissinger confronted the stark divisions caused by the superpower rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union. The contest was truly global in nature: political, ideological, military, nuclear, geographical and cultural.

But it was also essentially two-sided: at its crudest, the Free World versus the Reds. Today, as Kissinger admitted in recent interviews, the world has grown more geopolitically complex – multipolar, multilateral, multidimensional. Nations assert themselves. Non-state actors proliferate. Globalisation creates odd bedfellows. The age of deference to superpower has passed. Hegemony is just not what it used to be.

It is difficult now to conjure up the fear, paranoia and sheer ignorance that often characterised those cold war years, long before the advent of instant mass communications and the internet. Scares about “Reds under the bed” and imminent nuclear Armageddon were only too real. Distrust was pervasive and corrosive.

Kissinger shared in the general western antipathy to communism in whatever form, real or imagined. In particular, Chinese communism, after the revolution that brought Mao Zedong to power in 1949, was considered mysterious and threatening.

Having fled for his life from one totalitarian regime in Hitler’s Germany, Kissinger must surely have felt some personal misgivings about engaging amicably with another in Beijing. Yet, secretly and with typical cunning, at Nixon’s behest, he set out to do just that in the early 1970s.

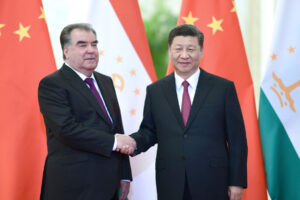

It was a prime example of the sort of realpolitik that became closely associated with his name. His discussions bore fruit and in 1972 Nixon stunned the world by travelling to meet Mao in China’s capital. Formal diplomatic relations commenced in 1979.

It’s unlikely Kissinger or Nixon had any premonition of the astonishing pace and scale of China’s development over the ensuing decades. Today, the bilateral relationship between the two largest economies is the most important, and increasingly the most fraught, in the world.

Yet, ironically, Nixon’s and Kissinger’s underlying, possibly principal purpose in opening up to China was to wrongfoot the Soviet Union, whose own ties with Beijing were strained. By playing “the China card”, they shifted the balance of power – a Kissinger obsession – in what they perceived to be Washington’s favour.

In the short term, at least, the manoeuvre worked. Kissinger, as an academic, had once argued it was possible to win a limited nuclear war. But reducing the vast Soviet nuclear arsenal through negotiation was a less hazardous proposition.

Surveying the US-China rapprochement, the Soviet leader, Leonid Brezhnev, turned more amenable to arms control talks. These formed part of the wider policy, embraced by the West German chancellor Willy Brandt and others in Europe, of what Kissinger called detente.

Detente with the Soviets had its critics, notably on the right of Nixon’s Republican party. But it led, in time, to a series of confidence-boosting nuclear arms limitation treaties.

Yet looked at from a different perspective, Kissinger’s “realist” attempt to balance the Soviet threat, not unlike his juggling of China policy, was severely limited in scope. In order to work, it deliberately ignored systemic Soviet human rights abuses, exemplified by ill-treatment of the dissident, Andrei Sakharov, winner of the 1975 Nobel peace prize.

Nor did Kissinger’s policy curb the global, as opposed to bilateral, aspects of US-Soviet rivalry. Present-day Iran is routinely censured by the west for backing proxy forces in Yemen and elsewhere. Its actions are as nothing compared with what Nixon and Kissinger got up to in the 1970s.

Throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa, in countries such as Mozambique, Angola, South West Africa (now Namibia), Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), rival forces covertly armed and equipped by Russia or the US fought each other for power and resources.

Latin American countries suffered similar traumas, with the most infamous proxy confrontation centred on Cuba. Yet regimes in developing countries whose geopolitical orientation suited the White House, such as the apartheid rulers of South Africa, received tacit US approval and support.

Moscow and Washington also competed for advantage in the Middle East, whose oil wealth assumed strategic importance after the so-called 1973 Opec oil shock sent crude prices spiralling globally.

The term “shuttle diplomacy” came into common parlance during this period, after Kissinger commuted between Israel, Egypt and Syria, mediating an end to the 1973 Yom Kippur war. His contacts with the Egyptian president, Anwar Sadat, are credited with opening a path to the Camp David accords.

Those accords led, in turn, to the breakthrough 1979 Egypt-Israel peace treaty, for which Sadat paid with his life in 1981. As a byproduct of this process, Soviet influence in the Middle East was greatly reduced. Not until 2015 did Russia return in force, given a free pass by Barack Obama’s refusal to intervene in Syria’s civil war.

However celebrated at the time, Kissinger’s approach to the big questions of his day – the China conundrum, the Soviet threat, Middle East instability – failed to produce lasting remedies. All three still pose daunting challenges for the US and its democratic partners.

But in other crucial respects, the world has changed radically. Viewed from the standpoint of what Robin Cook, a former British foreign secretary, called “ethical” foreign policy, much of what Kissinger did, encouraged or held indirect responsibility for now appears inexcusable, shocking and reprehensible.

The Vietnam war, which ended with the fall of Saigon in 1975, stands out for all the wrong reasons. Now widely regarded as a disastrous misadventure on a par with the 2003 Iraq invasion, it was brought to a conclusion through the Paris negotiations. Controversially, Kissinger was jointly awarded the 1973 Nobel peace prize for his role.

Yet his ruthless actions preceding his “peace with honour” appear horrifying now, most infamously the 1969-70 secret carpet-bombing of neutral Cambodia, where Vietcong forces were believed to be hiding out. Kissinger reportedly ordered the US air force to strike “anything that moves”. About 50,000 civilians died.

Such homicidal insouciance, leading over the years to multiple post-facto accusations of war crimes, reflected the darker, repulsive side of Kissinger’s realpolitik. His need for order and fawning respect for power induced him to deal with, even sometimes to coddle and appease, the powerful, however base.

But for the powerless, he had little time and less mercy.

Into this latter category fell the people of Chile, who had the temerity in 1970 to elect a leftwinger, Salvador Allende, as their president. For Chileans, it was a chance to forge a socialist future. For Kissinger and Nixon, it was further evidence of the spread of communism in America’s back yard.

The White House solution, backed by the CIA, was to support a military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet. A nightmare period of dreadful repression ensued, during which thousands were extrajudicially murdered.

Arrogant disregard for democratic choice, national sovereignty and human rights became a callous Kissinger trademark – notwithstanding the fact these were supposedly core American values. Like Pinochet, dictators in Argentina, Brazil and Central America basked in the warmth of Washington’s hypocritical approval.

Nor did Kissinger confine his concept of ruthless realpolitik to the western hemisphere. When East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, seceded from Pakistan in 1971 amid large-scale violence, Kissinger gave his private backing to Islamabad despite evidence, gathered by his own diplomats, of genocide by Pakistani troops.

In Oval Office tape recordings that emerged after the event, Kissinger was heard sneering at those who “bleed” for “the dying Bengalis”. He showed similar contempt for East Timorese civilians butchered during Indonesia’s US-backed 1975 invasion, again undertaken on the pretext of battling communism.

How could a single, albeit unusually powerful, diplomat from the world’s most powerful country, behave in such a wilful, arbitrary and seemingly criminal manner with evident impunity? The answer surely lies in the way the world has changed in the past half century.

Expanded UN-backed institutions, NGO watchdogs, international courts and ubiquitous digital media have rendered governments and individuals more accountable and scrutinised than ever before.

Another key factor, already noted, is the decline in social deference. Modern generations are less likely simply to do or believe what they are told by powerful men. The corollary is a decline in trust in governments, particularly striking in the US.

People in power do not necessarily behave better these days. But if they transgress, they are more likely to be exposed.

In his personal life, too, Kissinger got away with a lot. Those who knew or worked with him have described him as vain and hot-tempered as well as gifted, occasionally charming, and brilliant. At the White House, he provided the intellectual clout Nixon lacked. And like Nixon, he was unscrupulous.

More than once Kissinger tapped phones of staff he suspected of leaking information to the press. Reflecting the culture that led to the Watergate scandal, he evidently felt untouchable. When quizzed about such criminal behaviour, he quipped: “The illegal we do immediately. The unconstitutional takes a little longer.”

Kissinger spent his later years – he left the White House after Gerald Ford’s 1976 defeat to Jimmy Carter – running an exclusive consultancy, Kissinger Associates, advising presidents off-the-record, writing books and cultivating the image of respected elder statesman.

As the decades passed, people tended to take him at his word, forgetful of his record. Did the traumatised 15-year-old German Jew who washed up in New York as a refugee ultimately find the acceptance and security he craved? Perhaps. Will his reputation as a great statesman stand the test of time? Perhaps not.

Would Kissinger worry about that? No. In his world, what he loved best was the holding and exercise of power. And for a while, back then, few men were as powerful as he.

Source: The Guardian