By not attending Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s party at the G-20 summit in New Delhi, Chinese President Xi Jinping effectively signalled that the group no longer matters in geo-economic and geo-political terms. What matters is the G-7 and its direct competitor BRICS. And if the South African edition of BRICS is the sign of times to come, then this is where the world is converging. However, to convey China’s core message to the world that it favours globalisation, it sent Premier Li Qiang to attend the G-20 summit.

Protocol could be another reason why Xi may have decided to miss the Delhi jamboree since Modi would have given exceptional attention to US President Joe Biden. Moreover, to communicate that bilateral ties were at an all-time low, Xi did not bother to personally convey his absence to the Indian prime minister.

Except for the US, all nations believe that the world is moving towards multipolarity with two overarching global visions led by the US and China respectively. Therefore, so long as they are not pushed to choose between the two visions, nations are hopeful of drawing benefits from both. What is underplayed is the reality that global prosperity ultimately hinges on the success of the fourth industrial revolution underpinned by Artificial Intelligence (AI).

This software driven revolution with its competing standards, rules, norms, and regulations for the two visions will compel the nations to choose between them for digital commerce, trade, and navigation. And this may happen as early as 2030. In geopolitical terms, this means that unless the US endorses globalisation in totality (trade, commerce, and especially technology, which is unlikely), early signs of bipolarity fragmented between the two visions may emerge by the end of this decade.

India, which is a key geopolitical pivot in the Asia Pacific – where the two visions will play out – has chosen to align itself with the US vision. Moreover, unwilling to adjust with the risen (not rising or emerging) China, India has picked competition over cooperation with Beijing

Speaking at the Asia Society India on September 13, 2022, external affairs minister, S. Jaishankar said that a multi-polar Asia is necessary for the Asian century and multi-polar world, implying that India and China are equal poles in Asia and the world.

Zbigniew Brzezinski’s The Grand Chessboard (1997) published by Basic Books.

Jaishankar has clearly not read or understood Zbigniew Brzezinski’s book, The Grand Chessboard, which is a fascinating treatise on global strategy. According to Brzezinski, geo-strategic players are those nations which have the capability, capacity and political will to influence events beyond their borders. The US, China, and Russia fall in this category as distinct from major powers like Germany, France, the UK, Japan and the like. Thus, all geostrategic powers are major powers, but all major powers are not geostrategic players. Interestingly, in today’s world, major powers should be assessed by their technological prowess (as the fourth industrial revolution builds on the third revolution). This is central to both economic and military power.

Based on power in the field of technology – AI and emerging technologies which converge into it – India is not in the global game. Yet, being a significant geopolitical pivot, whose importance is derived not by its national power, but by its sensitive location, India is being courted by all three geostrategic players. Besides its geography, which sits astride the 3,000 nautical miles sea lanes of communication from the Strait of Hormuz to the Strait of Malacca – through which China’s four trillion dollars trade passes annually – India is also a huge market

The added attractions for the US are India’s massive, disciplined military; it being the biggest arms importer in the world; and the Modi government’s belief that a tight US embrace will help it to compete in the region with China. Before discussing why India’s strategy as it is evolving may end up being a dangerous self-goal, there is need to understand the two global visions.

Two global visions

The US vision seeks a replay of the Cold War where containment of the Soviet sphere of influence (politically and militarily) by deterrence, without a direct war between the two blocs, eventually led to the USSR’s demise along with the Warsaw Pact

At the same time, the US created the Bretton Woods institutions – the World Bank and International Monetary Fund – for global economic integration. It dominated the world by its exceptional military-industrial complex, established some 760 military bases across the globe, led the military-technological revolution, and ushered in the third industrial revolution, pivoted on chips and the internet.

In the unipolar scenario, from 1991 to 2017, the US ruled the world based on its military and dollar dominance. It toppled governments through colour revolutions, wars, and sanctions to propagate a hegemony that sought to build a world in which its corporations and military would have full freedom. Its official ideology emphasised the importance of democracy and human rights, but these were mostly expedient slogans to further Washington’s global interests.

Just as the US was fighting small wars, especially in Afghanistan and Iraq, by 2010, it realised that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) could match the US military in the west Pacific. The PLA had operational systems and guided munitions that, it noted, were as capable as its own. The PLA could close the kill chain as quickly as the US military. It could also conduct stand-off precision attacks at long ranges as well as the US military with its indigenous mortars, rockets, missiles, and artillery projectiles most of which were guided.

Coupled with miniaturisation, guided weapons brought unprecedented lethality at long ranges. This led the Pentagon to announce the third offset strategy driven by AI and autonomy in 2014.

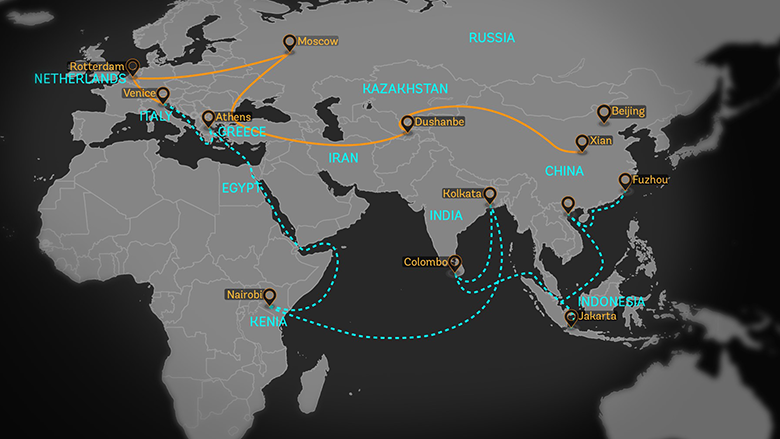

Incidentally, China announced its One Belt One Road (or Belt and Road Initiative) project in 2013 followed by the Digital Silk Road in 2015. With expertise in destroying nations but none in building them, the US was at sea in the face of numerous challenges presented by China:

- Its exceptional capability and capacity in international infrastructure building,

- deep pockets to fund the BRI,

- military capability in the domains of space, cyber, and electromagnetic spectrum, and land-based missiles,

- its intense integration with the world economy whereby China was the major trading partner of over 140 nations and regions,

- it being the largest global manufacturer and trader in goods. This made terms like decoupling, de-risking, and diversifying difficult to carry through,

- its exceptional civil-military fusion for developing AI ecosystem, and

- its ability to commercialise AI incubated in the US (Silicon Valley).

Since AI is built and not bought off the shelf, China, by 2017, could lead the US in three of the six stacks which comprise AI. While lagging behind the US in AI hardware, software, and human resources, China excelled in data management, applications (for commercialisation), and integration or Internet of Things (IoT, also called internet modules). This started a tech war with the Trump administration banning Huawei 5G in 2018 followed by denial of chips, chip-making design software and tools to China by the Biden administration.

Unable to match China’s BRI, the US started maligning it by calling it a ‘debt trap’, underplaying the fact that 138 nations from the Global South were on board. Moreover, the US with its G7 partners also dabbled in half-baked connectivity projects like Build-Back-Better-World, Global Gateway, and recently the Indian-Middle East-Europe project unveiled at the G20 summit in India. These projects, if they ever fructify, will likely supplement the BRI rather than challenge it.

Meanwhile, the Biden administration decided to double down on its own strength by turning the Obama administration’s 2011 ‘pivot to Asia’ policy into ‘integrated deterrence’ by aligning allies, strategic partners (India) and the Atlantic-specific NATO into its Indo-Pacific defence network. It was lost on the US that there is no military answer to the BRI: a strategy built on expansion of commerce, trade and navigation by connectivity, AI, and big data.

If the US continues to be driven by containment and global domination, China speaks about ‘global respect’. It asks that nations onboard the BRI framework – which includes the SCO and the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union nations – remain sensitive to China’s interests while framing their foreign policy. To achieve this vision, China has enunciated what it terms its Global Development Initiative (GDI), Global Security Initiative (GSI), and Global Civilisation Initiative (GCI) concepts, working under the United Nations umbrella.

Aligned with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2030, GDI is expected to create green, efficient, and cost-effective development given China’s lead in Lithium-ion batteries, solar batteries, and new energy vehicles through BRI which will offer a mix of physical, mobile, and digital economies to the Global South nations.

The mobile economy, whose inflection point in China came in 2014, is about mobile internet, 4G networks with consumers in the lead. This mobile economy with imported hardware was offered to the world recently by India as a highpoint of its G-20 presidency. Moreover, since China has a lead over the G7 nations in rolling out a 5G network, the inflection point for a digital economy based on AI, data, cloud, and blockchain came in 2017 in China. The digital economy led by enterprises is about the industrial internet where, given China’s expertise in software, it is ahead in the internet module or IoT.

Fast forward to some possible scenarios, three to five years from now.

Large Language Models (LLMs) like Chat GPT-4, which took the world by storm in 2023 by its generative AI, will be hundreds of times larger with exceptional capabilities. Instead of generating text, the new LLMs will be able to generate sequences of actions to be done and then be able to do them by itself.

Given its lead in the industrial internet on account of 5G availability at scale, China will likely focus its LLMs not on Natural Language Processing (NLP) to generate text, videos, and images like Chat GPT, but on the SDGs underpinning the GDI.

For example, since the LLMs will be able to generate AI which could communicate and negotiate with humans on the phone and interact with other AIs to ensure glitches in supply chains are removed quickly, they will have tremendous uses in health services, smart logistics, smart cities, digital finances, biotechnology, and other applications of the fourth industrial revolution.

LLMs will also have a big role in the creation of the metaverse or the next generation of the internet. The convergence of virtual reality and a digital second life (avatars) will be boosted by generative AI for business models, trade, and commerce. Thus, the technology layer underpinning the metaverse will comprise AR/VR (Augmented Reality/Virtual Reality), IoT, 5G, 6G, and mesh network which self-organise and self-configure nodes for efficiently routing data to and from clients.

From the above, two things become clear – one, the need for cyber security against backdoor and adversarial attacks, and second, to set standards, norms, regulations, and roles for new technologies of the fourth industrial revolution.

Since the US is determined to obstruct China’s innovations, the tech war started by the US will intensify. This is likely to result in the splintering of the internet and eventually fragmentation of industrial supply chains for trade and commerce. Given this, it will become increasingly difficult for nations aligned with the two global visions to trade with one another digitally.

Furthermore, most Global South nations have been attracted by GSI whose basic premise is indivisible security, implying a no zero-sum game or one’s security at the cost of another’s security. Simply put, instead of absolute security, nations should consider relative security. GSI also advocates an end to unilateral sanctions (outside the UN) and bloc confrontation, as well as non-interference in the internal affairs of other nations. It also advocates respect for each nation’s traditions and values – as against the instrumentalist ‘universal values’ for human rights, democracy, and empowerment which, as we noted, the US pursues only selectively. In a fast-fragmenting world, all nations, especially big ones like India, will have to choose a side. ‘Balancing’ may no longer be an option.

Thus, senior Indian analysts’ contention that India should remain engaged with BRICS, the SCO, QUAD, and the G-7 nations as this would increase its diplomatic options in a polarised world is not sustainable.

G-20

India’s presidency of the G-20 summit will be remembered for two things.

One, the absence of Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi, whose nation’s economies, according to IMF 2023 figures, grew faster than any other G-7 nation. After the spectacular success of the BRICS 2023 summit in Johannesburg, the answer to US’ dollar dominance was found in trading in local currency and BRICS Pay (this will not replace, but displace SWIFT), an electronic banking system which Iran will join in January 2024 amongst other nations.

Moreover, the inclusion of the African Union as the new G-20 member was a pyrrhic victory compared with the six new members added to the BRICS (these include all global major energy exporters and importers) given that 50 of the 54 African nations attended the 2023 BRICS summit. With $300 billion annual trade, China is the largest trading partner of the African continent and Russia is the biggest arms exporter. Thus, while China is the undisputed leader of Global South, to humour India, the US and G-7 have endorsed it as the voice of Global South.

Second, the Delhi G-20 joint declaration was made possible not because of Prime Minister Modi’s foresight or India’s exceptional negotiating skills but because India is a major geopolitical pivot wooed by the US, and not yet abandoned by China and Russia. The Delhi declaration was a watered-down version of the Bali G-20 declaration since for the US, the bilateral Modi-Biden meeting before the official G-20 summit was far more important that the joint statement which had nothing to do with the reality of the Ukraine war. Modi had one-on-one meetings with most G-7 nations since they, like the US, have stakes in the Indo Pacific region which may be decisive factors in global geopolitics.

Given the US’s support to India’s G-20, which comes close to India’s general election in 2024, it would be natural for Biden to want a quick execution of the joint declaration signed during the Indian prime minister’s visit to the US in June. Washington does not want India to go the Australia way, which, while being a member of both QUAD and AUKUS, is now busy improving its trade ties with China, or like Malaysia which has decided to downplay China’s new map which infringes its sovereignty, in favour of improving prospects for trade with China.

Modi’s gambles

India’s silence on China, despite cozying up to the US, will have its limits if really pushed to the brink. Ever since the Galwan episode in June 2020, India has gone quiet on even its other neighbour, Pakistan, with it not making its usual appearance in election rhetoric. With a tendency to see everything through a prism of its domestic audience, China and Pakistan being aligned poses a graver challenge to India’s ruling party’s politics than is acknowledged.

Since good geopolitics is and should be rooted in geography, India’s statecraft should concentrate on decent relations with Pakistan and China. If India was honest with itself, it would know that PLA’s April 2020 incursions into Ladakh were the consequence of India creating a new map after the revocation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir on August 5, 2019) which resulted in a Union Territory (UT) status for Ladakh. Conscious of this fact, and China’s displeasure, external affairs minister Jaishankar travelled to Beijing on August 11, 2019 to explain that India’s new map would not change the reality on the ground. China rejected his explanation and changed reality on the ground in Ladakh.

Sadly, the Indian military (medium power) risks being outflanked by the PLA’s (major power) in case of a confrontation and this challenge has three dimensions.

One, as against the Indian military, which will wage combat across physical battle spaces comprising land, air, and sea domains, the PLA will likely engage four battles paces. Its physical battle-space will comprise land, air, sea, outer space, and near-space (for hypersonic missiles) domains. The virtual battle-space will include cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum. The information battle-space will have wired and wireless networks through which data passes. And the cognition battle space – where an information war will be unleashed – will involve a mind war, which will entail assaulting the enemy’s judgement. The PLA is likely to emphasise cognitive confrontation and push to seek an early cognitive victory.

Two, unlike the Indian military, the war fought by the PLA will not be confined to a battlefield or combat space. And three, China will not fight a tactical war at the frontline where the Indian army has an advantage, but across the entire combat zone at the operational level where the outcome of the war will be decided.

Given all this, never has it been more critical for India to improve relations with its neighbour, China. It’s not just about tactics, but about being on the right side of history.

Source : TheWire