Gabriel Sterling, a senior Georgia election official, is no stranger to the rough and tumble of politics. But he lost his temper over the death threats he witnessed during the 2020 vote count, including a social-media post that featured a swinging noose and exposed the name of a Dominion Voting Systems tech worker.

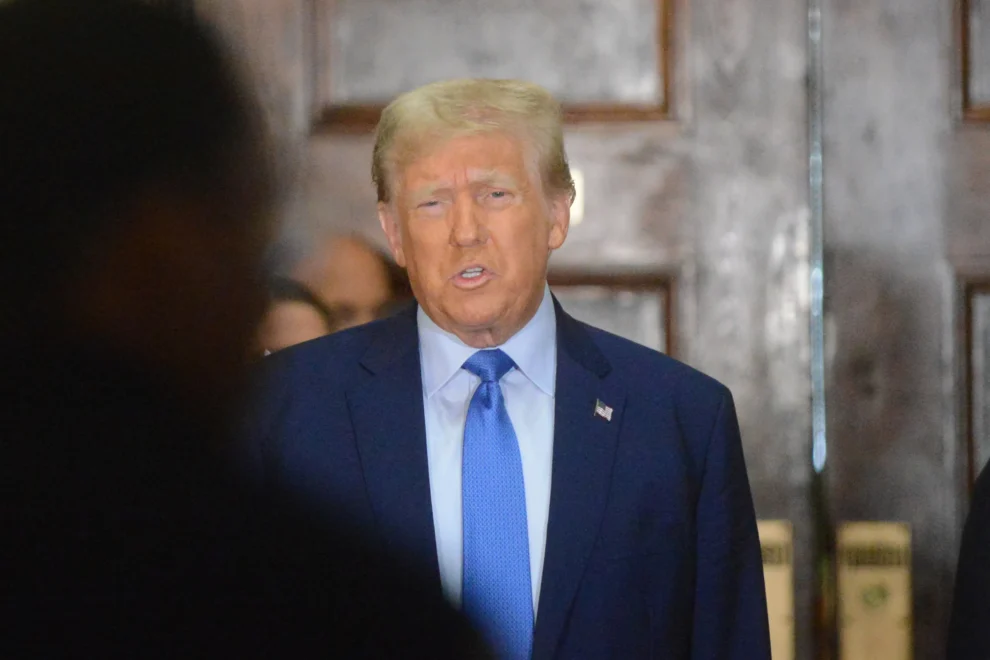

“It has all gone too far,” Sterling, who had police protection himself, told reporters Dec. 1, 2020, while imploring then-President Donald Trump to show leadership and condemn the threats. “Someone is going to get hurt. Someone is going to get shot. Someone is going to get killed.”

Critical posts keep coming. One of Trump’s 18 co-defendants in the Georgia election racketeering case, which charges them with trying to overturn the election results, referred to Sterling with an emoji of poop. Sterling testified he didn’t like being called a piece of poop, but didn’t consider it a threat.

While most defendants remain mum before trial and often decline to testify, Trump and his co-defendants have vocally protested their innocence and criticized their prosecutions. The court decisions will be crucial to Trump, who demands on the comment on the cases while campaigning for president in 2024.

“It’s rare that you have criminal defendants who have the megaphone that a former president does or that other high-profile defendants have,” said Alex Reinert, a criminal law professor and expert on criminal procedure at the Cardozo Law School. “I think in Mr. Trump’s case it seems less about the criminal case and more about his campaign and about airing grievances that will resonate with his base.”

What gag orders do Trump, co-defendants face?

Judges have restricted speech in three Trump cases:

- The New York judge in Trump’s civil fraud trial, Arthur Engoron, ordered Trump and his lawyers not to comment on court staff, including clerk Allison Greenfield, who was criticized repeatedly for allegedly influencing Engoron. Engoron fined Trump a combined $15,000 for two violations. Trump appealed, but an appellate panel restored the gag order while the dispute is argued.

- U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan, who is presiding over his federal election conspiracy case, ordered Trump not to comment on court staff, prosecutors or potential witnesses. Trump appealed to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, which heard oral arguments Nov. 20.

- Trump’s bond agreement in his Georgia election racketeering case requires him not to contact witnesses or co-defendants to discuss facts of the case and not to directly or indirectly threaten witnesses or co-defendants, including through social media posts. Prosecutors asked Fulton County Superior Judge Scott McAfee to revoke the bond of one of Trump’s 14 remaining co-defendants, Harrison Floyd, for posting on social media about witnesses in the case. But McAfee refused and instead asked for new restrictions on Floyd’s comments.

“It’s a delicate balancing that the courts are going through,” said Derek Muller, a lawyer professor at the University of Notre Dame. “I envy no one in trying to balance them in a case like this.”

Conservative states, ACLU oppose Trump gag order

In his appeals, Trump challenged the New York and federal gag orders as overly broad and vague.

Engoron forbade “all parties from posting, emailing or speaking publicly about any members of my staff.” But Trump’s lawyers accused Greenfield of being a partisan Democrat with undue influence over Engoron and thus a fair subject for his criticism.

Chutkan prohibited Trump or his lawyers from making public statements that “target” prosecutors, court staffers or witnesses. Trump could comment on the Justice Department or the campaign platforms of rivals such as former Vice President Mike Pence, a potential witness in the case, she ruled. But Trump lawyer John Sauer argued the term “target” is so vague it could chill more speech than intended.

“To date, the prosecution has never submitted any evidence of alleged ‘threats’ or ‘harassment’ to any prosecutor, court staffer, or potential witness in this case,” Sauer wrote in one filing. “Both the indictment and the Gag Order represent an unconstitutional attempt to silence President Trump; they are clearly election interference.”

Attorneys general from Iowa, West Virginia, Alabama, Alaska, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Oklahoma, and Utah argued the federal case “does not justify the district court’s slapping President Trump with this prior restraint.”

“That overbroad Order − an order that a major United States presidential candidatemute himself on a major campaign issue − cannot survive any level of scrutiny,” wrote Eric Wessan, the Iowa solicitor general, wrote for state Attorney General Brenna Bird.

The American Civil Liberties Union opposed the New York gag order, arguing that the restriction against “targeting” court staff, prosecutors or witnesses was too broad and should be narrowed to cover only comments representing imminent threats that would impede a fair trial.

“No modern-day president did more damage to civil liberties and civil rights than President Trump, but if we allow his free speech rights to be abridged, we know that other unpopular voices − even ones we agree with − will also be silenced,” said Anthony Romero, executive director of the ACLU.

Curbing political speech during the presidential campaign?

Even without gag orders, Trump’s handful of pending trials could distract from his presidential campaign. Restrictions on his speech − if upheld − could make it harder for him to combat the various allegations in the court of public opinion.

His New York civil fraud trial, which could potentially liquidate his business and result in millions of dollars in damages, is ongoing. E. Jean Carroll has a civil trial scheduled for damages in a defamation case against Trump scheduled for Jan. 15 − the same day as the Iowa caucuses. His federal election conspiracy trial is scheduled March 4, in the heart of the primary season.

Trump’s lawyers − Christopher Kise, Alina Habba and Clifford Robert − have railed against restrictions on his First Amendment right to speech in the fraud case. They argued Engoron was acting as “judge, jury and executioner” in fining Trump in a “Star Chamber approach” to his New York gag order. Sauer called Chutkan’s gag order in the federal case a “heckler’s veto.”

Trump has consistently attacked the criminal cases against him as political prosecutions and adversaries in civil cases as Democratic partisans. His comments paused under gag orders and rekindled when they were lifted for appeals. He sent a fundraising solicitation Thursday talking about “radical Democrats” censoring him the same day the New York appeals court restored the gag order.

“The key for Trump is to portray the prosecutions as a politically motivated witch hunt,” said John Pitney Jr., a politics professor at Claremont McKenna College. “That way, his voters would view a conviction not as proof of his guilt, but as a sign of his victimhood. That’s why he keeps repeating the phrases ‘witch hunt’ and ‘election interference.'”

Could Trump be jailed for violating a gag order?

The typical sanctions for contempt of court for violating a gag order or bond agreement range from fines to imprisonment.

When Engoron initially fined Trump $5,000 − for leaving a post about the clerk online for two weeks − he threatened “more severe sanctions” including “possibly imprisoning him.”

For the second violation, Trump denied calling the clerk partisan during remarks outside the courtroom and said in sworn testimony he was referring to a witness, his former lawyer Michael Cohen. But Engoron called Trump’s explanation “not credible” and fined him another $10,000.

Chutkan could fine Trump for potential violations in the federal case, if her order is upheld on appeal.

But legal experts said potential jail time would depend on the type and severity of the violation, if infractions continued after escalating fines.

“I think any judge would first try to compel compliance with the order through the use of fines before taking away someone’s liberty,” Reinert said.

Muller said imprisonment traditionally is used to induce action, such as turning over documents, rather than curbing action, such as talking. Trump could potentially violate the gag orders intentionally, to demonstrate his defiance and provoke a confrontation.

“With former president Trump, you never know if it becomes something of a martyr complex,” Muller said. “I would never rule it out.”

Georgia judge declines to jail Trump co-defendant over posts

Trump isn’t the only one threatened with imprisonment for comments about the charges.

In the Georgia case, Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis sought to revoke Floyd’s bond and jail him pending trial for social media posts that violated his bond agreement, such as the ones tagging Sterling with poop emojis.

Jenna Ellis, another co-defendant in the case who pleaded guilty and is now a witness, told investigators through her lawyer that Floyd’s posts about fundraising for her defense were “meant to intimidate and harass me.”

The judge, McAfee, ruled Floyd technically violated his bond agreement by contacting witnesses indirectly, but that he shouldn’t be jailed. McAfee ordered prosecutors and defense lawyers to tighten the restrictions in Floyd’s bond agreement.

“Mr. Floyd seems very boldly willing to explore exactly where that line lies in this case,” McAfee said. “I read these as seeing more that someone is wanting to defend his case in a very public way.”

Floyd’s initial bond agreement restricted him from intimidating witnesses or co-defendants in the case, or communicating with them directly or indirectly, but didn’t mention social media as Trump’s agreement did.

The revised bond agreement bars Floyd from making any social media post about any witness or co-defendant in the case, including by mentioning, tagging or liking posts of others, and required him to delete previous posts that violated the rule. The order also prohibited Floyd from making any public statement about any witness or co-defendant, including through books, newspapers, magazines, television, radio, podcasts, YouTube or Rumble.

Source: USA Today